The terrifying rise of the Islamic State (IS/ISIS/ISIL/Daesh) has produced perplexity and political paralysis among self-proclaimed Marxists. Perhaps the best example of both is Anne Alexander’s “ISIS and Counter-Revolution: Towards a Marxist Analysis” which failed to investigate a single question of interest to Marxists:

- What is the class basis of IS? What class or classes constitute its social roots?

- What type of political order does IS fight to establish (monarchist, theocratic, democratic, socialist, communist, fascist)?

- Is IS progressive or reactionary, revolutionary or counter-revolutionary?

- What is to be done about IS?

The inadequacy of Alexander’s analysis became exposed during a subsequent debate with Ghayath Naisse, an exiled Syrian Marxist, who noted that IS displays certain “fascist characteristics.” Alexander rejected the comparison and argued that “the differences between IS and fascist movements are more important than the similarities” on the following grounds:

“First, the context in which ISIS has arisen in Iraq and Syria differs significantly from both the historic context in which European fascist movements arose and the context in which their successor movements operate today. Secondly, the role played by fascist movements in confronting and ultimately defeating the organised working class is absent in ISIS’s case (although this is because the working class is practically absent as an organised actor in Syria and Iraq and not because ISIS is ideologically or practically less hostile to working class self-organisation). Thirdly, ISIS is not organised in a similar social movement form to fascist movements. In its heartlands it operates principally as an army that claims state authority, rather than as a political movement with an armed wing. It is certainly not a mass movement, but rather an elitist vanguard of fighters whose political impact is predicated on their military capabilities, not the other way around.

“ISIS is in essence an armed faction, which has emerged in the context of insurgency and civil war, rather than a social movement. This does not mean it is irrelevant to ask questions about the organisation’s social base—its soldiers and commanders may well be drawn largely from specific social backgrounds. But it is another crucial point of difference with fascist movements, which historically proved able to deploy paramilitaries along with civilian organisers in a single coherent movement.”

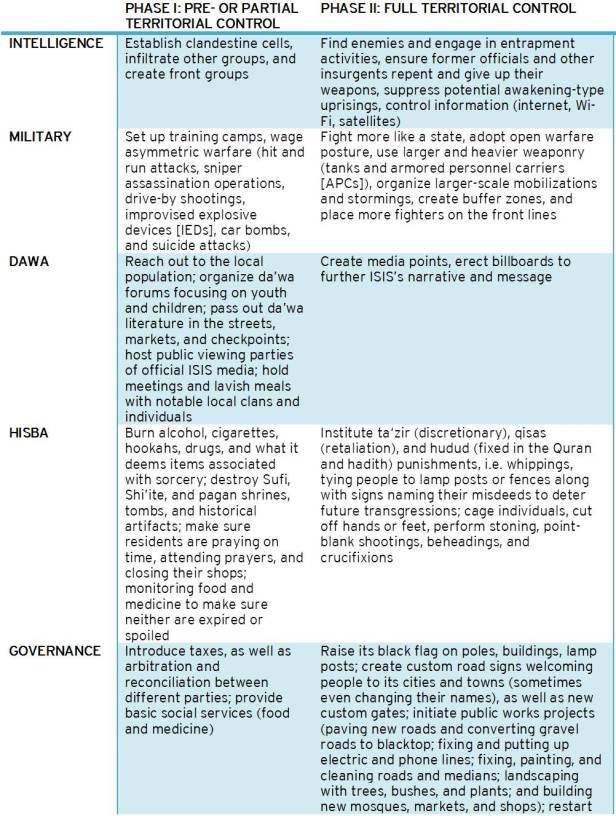

Here, Alexander makes the same mistake about IS that Italy’s young Communist Party made about Mussolini’s blackshirts by “regarding [them] as merely a militarist and terrorist movement without any profound social basis,” as veteran communist Clara Zetkin put it. Alexander’s second mistake: IS does use civilian organizers in its heartlands to spread its message among the masses, hold rallies, develop networks of informants and spies, enforce its moral strictures, and recruit fighters. These movement activities are conducted under the guise of Islamic missionary work (Dawah).

But even if Alexander were correct that IS is not a social movement but an armed faction that emerged in a context of insurgency and civil war, that tells us nothing about what distinguishes IS from the plethora of other armed factions that emerged in the same context. Syria and Iraq are full of armed factions (nationalist, Sunni Islamist, Shia Islamist, and even Marxist) but only IS launches terrorist attacks across the globe, only IS sets up markets to buy and sell women and girls as sex slaves, only IS sparked the formation of coalitions of states and proxy armies — one led by the U.S., the other by Russia — to wipe it off the face of the Earth.

Any analysis of IS that cannot account for these differences is worthless.

Understanding Fascism

Before comparing IS to fascism, we must first understand fascism. As George Orwell pointed out in his 1944 essay “What Is Fascism?,” there is no widely accepted, theoretically rigorous definition of fascism and this is true for Marxists as well.

Clara Zetkin argued in 1923 that “fascism is the concentrated expression of the general offensive undertaken by the world bourgeoisie against the proletariat” and observed that “fascist leaders are not a small and exclusive caste; they extend deeply into wide elements of the population.” Building on Zetkin’s ground-breaking analysis, the Communist International’s leading theorist Georgi Dimitroff defined fascism in 1936 as “the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinistic and most imperialist elements of finance capital” that came to power by “gain[ing] the following of the mass of the petty bourgeoisie that has been dislocated by the crisis, and even of certain sections of the most backward strata of the proletariat.” Leon Trotsky similarly defined fascist rule in 1933 as “the most ruthless dictatorship of monopoly capital” and fascism as “the mobilization of the petty bourgeoisie against the proletariat,” as a “means of mobilizing and organizing the petty bourgeoisie in the social interests of finance capital.”

These definitions cannot be treated as gospel since Mussolini’s and Hitler’s regimes adopted policies opposed by and detrimental to both finance and monopoly capital. Far from being the dictatorship of finance or monopoly capital (or big business generally), fascist regimes subordinate the interests of these classes to fascism’s ideological imperatives or political goals. The class relations this subordination entails are what distinguish fascist regimes from ordinary military dictatorships like Sisi’s Egypt or Pinochet’s Chile. All fascist regimes are dictatorships but not all dictatorships are fascist regimes.

Shortcomings aside, what the Marxist definitions get fundamentally right is that fascist movements are based on de-classed and/or downwardly mobile social strata. The class basis of a specific fascist organization is historically conditioned and depends on concrete political and economic circumstances. For example, the Great Depression swelled the ranks of the Nazis with millions of unemployed, ruined small businessmen, white-collar functionaries, and even housewives whereas Hitler’s 1923 Beer Hall Putsch was staged mainly by ex-soldiers demobilized after World War One. Rejecting comparisons of IS with fascism because conditions in present-day Iraq and Syria are “significantly different” from conditions in early 20th century Europe means a failure to grasp that fascist political trends exist — to one degree or another, in one form or another — in a great variety of social contexts such as 1980s Britain, post-communist Russia, or post-2009 Greece.

Accepting the obvious truth that fascism can and does arise in a range of social conditions gets us no closer to understanding either fascism’s essential characteristics or how IS measures up to them; for that, we must examine fascism’s aims and methods.

Fascism appears revolutionary because it upends old state forms and subordinates previously dominant classes. As a ‘revolution’ of the far right, fascism is fanatically opposed to both the socialist revolution and the democratic revolution. This makes fascism the enemy of not just socialists but of all democrats left, right, and center. Once in power, fascists do not limit themselves to eliminating bourgeois democracy, the political left, and the labor movement — the political right, business and professional organizations, independent media, and dissident trends within fascism are wiped out as well.

In early 20th century Europe, the chief obstacle to fascist takeovers was the labor movement with its millions of workers organized in trade unions and mobilized by socialist, communist, and labor parties. Painstakingly constructed over decades of struggle, these institutions and traditions became bourgeois democracy’s bulwarks when armies and parliaments acquiesced to fascist power-grabs like pathetic paper tigers. After Hitler came to power without a shot being fired in the German labor movement’s defense, the Austrian labor movement resisted fascism by force, the French labor movement aborted fascism’s rise by forming a Popular Front, and the labor-led Popular Front government in Spain waged war to save the democratic republic from Franco.

As the far right’s rejoinder to Bolshevism, fascists exploit political freedom in order to destroy it by skillfully combining the use of both legal (peaceful) and illegal (violent) methods. Behind the fascist politician in a suit wielding words stands the street thug wielding weapons. Violence or the threat of violence is crucial to fascism’s pseudo-revolutionary appeal. Despite their anti-establishment rhetoric, scapegoated minorities are the prime targets of fascist violence. They are the first to suffer when fascism is not ruthlessly stamped out during its embryonic stages of development.

To sum up: fascism is a movement based on de-classed and/or downwardly mobile social strata that upends old state forms and subordinates previously dominant classes. Although fascism appears to be revolutionary, it is in fact counter-revolutionary, hostile to both the socialist revolution and the democratic revolution. As shameless opportunists, fascists employ a combination of legal (peaceful) and illegal (violent) means to advance their cause and eliminate their enemies.

Islamic State and Fascism Compared

IS matches each of the aforementioned characteristics of fascism.

1. Based on de-classed and downwardly mobile elements. Like Hitler’s Beer Hall putschists and Mussolini’s Blackshirts, IS’s leadership and cadre are demobilized officers from the military and intelligence services. Occupied Iraq’s American dictator, Paul Bremer, created social conditions favorable to IS by obliterating the only institutions capable of providing what Frederick Engels called the state’s “public functions” — the army, police, judiciary, and health care, finance, and education ministries. With the stroke of a pen, Bremer not only fired hundreds of thousands of men with vast administrative and military experience but banned them from future government service, depriving them of secure incomes and definite places Iraq’s social order. To these men, IS promised to restore both in its 2006 declaration of statehood:

“… we call upon officers of the former Iraqi Army and that is from the rank of lieutenant to major to join the army of the Islamic State on condition that the applicant must know, at a minimum, three sections of the Holy Koran by rote and must pass an ideological examination by a clerical commission, that exists in every region, to make sure that he is not beholden to the idolatry of the Ba’ath and its tyrant [Sadda]. And we will, Allah willing, provide him with transportation, housing and the appropriate salary that guarantees an honorable life for him as is provided to the mujaheddin who fight under the banner of the Islamic State of Iraq…”

The average Syrian or Iraqi young man fighting for IS today comes from a rural impoverished area, has little formal education, and faces incredibly bleak prospects for earning a living as war unravels the Syrian and Iraqi economies. As one surrendered fighter from Iraq’s Hawija district put it, “When you are a young man and you don’t own 250 dinars and someone comes and offers you 20,000, 15,000 or 30,000, you will do anything.” (30,000 Iraqi dinars is roughly $26.) Syria’s unemployment rate is 60% and 83% of Syrians live in poverty; for Iraq, these figures are 40% and 31%, respectively. IS is a steady paycheck and for some, an opportunity for advancement up the class ladder. An unskilled laborer-turned-fighter can some day become an emir with power, prestige, a big house, a car, wives, children, and sex slaves. Economic disruption deliberately caused by the U.S.-led coalition’s bombing campaign has driven already-destitute Syrian families to send their sons to join the group as a means of supplementing their falling incomes.

Drawn by “the utopian appeal of religious enthusiasm that offers meaning to otherwise meaningless lives,” IS’s foreign fighters are often (but not exclusively) ‘losers‘ who come from the lumpenproletariat, particularly criminal elements. The group’s founder, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, was a pimp and drug-dealer; the Kouachi brothers of Charlie Hebdo fame relied on odd rather than stable jobs before going to prison on terrorism charges; the organizer of the Bataclan massacre, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, served time in prison for burglary and assault. Areas with the highest number of emigrants per capita also tend to have high levels of long-term unemployment either nationally (Kosovo, Bosnia, Tunisia) or in specific areas of the country (like Belgium’s Molenbeek neighborhood).

IS’s dependence on this specific combination of disparate class elements for manpower flows from a dearth of popular support for the group in Syria and Iraq. The destruction of the Syrian and Iraqi economies gives IS strength in the form of recruitment and yet this strength constitutes a fatal weakness from the standpoint of governance, of building a stable, sustainable polity within the 21st century world-capitalist nation-state system. Impoverished Syrians and Iraqis and petty criminals from abroad have neither the knowledge, the skills, nor the economic resources necessary to administer — let alone construct — modern states, institutions, and economies and the social classes that do continually flee IS territory. The resulting ‘brain drain‘ crippled the IS’s health care system even before the U.S. air war began in earnest. Furthermore, IS depends on Baghdad and Damascus to pay for critical infrastructure like clean water and to provide the salaries of skilled personnel needed to maintain it.

Far from being an economically viable, self-sustaining, self-contained Islamic paradise, IS is completely parasitic, dependent on hostile governments to provide basic services and reliant on criminal activity (confiscations) for nearly 50% of its income. The economy in IS-occupied areas is characterized by unending shortages of basic goods, skyrocketing inflation, falling agricultural output, high taxes and fees, and the failure of IS’s gold dinar to replace the Syrian lira, the Iraqi dinar, and the U.S. dollar. (Apostates and crusaders deserve to be killed, their governments overthrown, but using their money is evidently halal).

The contradiction between the steadily deteriorating of objective social conditions that allow IS to reproduce itself and the group’s inability to ameliorate those deteriorating conditions through governance doom IS to recreate the failed states it set out to replace, albeit in ‘Islamic’ form and with far less success.

2. Upend old state forms and subordinate previously dominant classes. IS employs a very successful divide-and-rule strategy against the previously dominant social force in eastern Syria and Western Iraq — the tribes, vast extended families and kindship networks that, prior to IS’s ascendance, controlled smuggling routes, commerce, oil production and distribution, security, and construction. IS has a ministry specially dedicated to manipulating tribal politics.

By integrating some and not other members of tribes into its political and military superstructures, IS ensured that any tribal revolt against its rule would necessarily mean a fratricidal struggle pitting members of the same families and clans against one another. When a popular uprising against IS by the al-Shaitat tribe in Deir Ezzor broke out in 2014, IS defeated the rebels by offering some of them amnesty if they ‘repented’ while the rest — 700 al-Shaitat men, women, and children — were slaughtered.

Another indication of tribal subordination to IS rule is the group’s systematic intervention into tribal disputes, some of them decades old. These disputes are resolved in accordance not with tribal custom but with IS’s ideological imperatives as expressed in their version of Islamic law (sharia).

3. Appears revolutionary, is actually counter-revolutionary. IS promises to bring down the murderous Assad regime and yet the first people in Syria IS systematically targeted for elimination were not regime stalwarts but the backbone of the popular movement against Assad — protest organizers, citizen journalists, local council authorities, and Free Syrian Army (FSA) commanders.

4. Use of legal (peaceful) and illegal (violent) means. IS is world famous thanks to its gratuitous violence but its use of legal and peaceful means is just as important although less well known. All over Europe, IS utilizes underground networks of supporters, sympathizers, and non-ideological criminal gangs to funnel people, money, weapons, and explosives to and from Syria and Iraq. Some of these networks are centered around fake charities and Wahhabist mosques (often unlicensed) financed by Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, or billionaires from these countries. There are hundreds of such mosques in Kosovo, Bosnia, Belgium, and France and it is no coincidence that these four countries contribute alarmingly high numbers per capita of European foreign fighters to IS. Groups like Sharia4Belgium and hate preachers such as Hani al-Sibai in Britain function as legal fronts for IS despite their independence from the group by finding potential recruits and gathering them together into common social milieus and networks. Al-Sibai directly influenced “The Beatles,” the four-man cell of British IS members led by executioner Jihadi John.

Although IS shares essential characteristics with traditional or classical fascism, it is obviously not a traditional or classical fascist group and possesses unique characteristics:

- IS does not take power with either the open support or tacit acquiescence of a state’s military.

- IS only takes state power in Sunni majority areas of the world where it can exploit vacuums created either by failed states (Syria), failed politics (Iraq), or both (Libya). (IS’s dependence on vacuums and chaos to take power is codified theoretically in its jihadist manual, The Management of Savagery.)

- IS’s appeal is not limited by nationality or ethnicity because its ideology is religious rather than nationalist or racist. Any person in the world can pledge allegiance (bayah) to IS.

- IS is not a threat to just to one nation or region but to the entire world because it ignores borders between existing states and obliterates them where possible. Countries not attacked by IS are still centers of IS activity in the form of recruitment.

These unique characteristics are due to IS’s roots in the transnational jihadist movement and therefore fascism with jihadists characteristics is the best way to understand the political content of IS’s aims and methods. In class terms, IS’s rule is best described as the dictatorship of the lumpenproletariat.

Islamic State versus the Ummah

IS’s declaration of a caliphate — an Islamic state ruled by a single authority (Khilifa or Caliph) with political and religious sovereignty over the entire global Muslim community (ummah) — guaranteed that there would be a significant religious and theological dimension to the struggle against IS. IS has not only been condemned but refuted in legal opinions (fatwas) issued by Muslim clerics (imams) from across Islam’s theological spectrum: Sunnis, Shias, Sufis, Salafists, Deobandis, Nahafis, and even the extremist Wahhabis. Unable to refute this litany of withering and scholarly Islamic criticism through argument, IS instead issued kill lists of imams in its magazine Dabiq.

This clash between the ummah and IS continually gives rise to clichés like ‘IS is not Islam’ or ‘IS are not Muslims.’ The truth or falsehood of such platitudes depend not on debates in seminaries between Sunni scholars or heated exchanges on Twitter but on real-world struggle between the ummah and IS. Condemnation and refutation are not enough; mobilization and organization are necessary to combat IS’s pernicious influence one believer at a time since even one wayward soul or deranged person can launch a murderous lone wolf attack.

This struggle of the ummah, for the ummah, by the ummah is a struggle in which non-Muslims can only play a subordinate, supportive role. Unfortunately, non-Muslim politicians in the West — eager to signal how virtuous and anti-Islamophobic they are — have publicly inserted themselves into this intra-ummah fight by mindlessly repeating the mantra that ‘IS is not Islam.’ By weighing in on religious matters, they make a mockery of the secular underpinnings of their political systems and make fools of themselves since they have no Islamic authority, credentials, or knowledge. The more forcefully liberal do-gooders insist that IS has ‘nothing‘ to do with Islam, the more Western electorates become cynical of such claims. All across the West, far right parties and candidates are riding this illiberal backlash to gain mass influence.

While classical or traditional fascists appear revolutionary by virtue of their anti-establishment rhetoric, IS leverages its fringe status within the ummah to portray itself as a small but righteous band of revolutionaries taking on a corrupt and complacent Sunni religious establishment for the sake of true or pure Islam. Unlike Ayatollah Khomeini’s movement in Iran, IS is not the political expression of any element of Islam’s clerical establishment and therefore its theocratic pretensions are fraudulent (IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi received his PhD in Islamic studies not from a renowned center of Islamic learning like al-Azhar but from Ba’athist Baghdad University).

Fighting Fascism with Jihadist Characteristics

Like any other fascist organization, IS must be eradicated. Yet neither Alexander nor other Marxists (see here, here, and here) mention this necessity in their analysis of the group. They have forgotten Zetkin’s words: “Whenever Fascism uses violence, it must be met with proletarian violence.” Fortunately, the oppressed and exploited are not waiting for academic Marxists to abandon their ivory towers of neutrality and abstraction to defend themselves.

Because IS is the world’s most powerful and widespread transnational jihadist organization, there can be no one-size-fits-all strategy to combat it, applicable to all nations where IS has provinces (wilayets), affiliates, members, and sympathizers. Forms and methods of struggle cannot be identical across vastly different economic, political, social, and cultural circumstances. What is appropriate in Syria — arming the Syrian-Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and FSA, providing them with close air support, and ending the civil war by means of a democratic transition away from Assad’s misrule — is inapplicable in France, for example. Nor can the partially successful anti-fascist Popular Front strategy of the 1930s be revived without major amendments. After all, IS is not a traditional fascist group and 20th century European-style mass workers’ parties and politicized industrial unions do not exist in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (nor could they given the non-industrial class structures of most MENA countries). Yet the principle undergirding the Popular Front of uniting those who can be united remains relevant as ever.

The struggle to defeat and ultimately destroy IS is both international and internationalist in nature: no state or people can do it alone or independently of the efforts of other states and peoples. The more nations and peoples come into conflict — the U.S. versus Russia over Assad’s fate; Iran versus Saudi Arabia over regional power and influence; Shia versus Sunni over existence; Turkey and its Syrian proxies versus the PKK and YPG over the destiny of northern Syria — the easier for IS to survive and prosper.

But just as the struggle against IS must be international and internationalist in character, it must also be bottom-up as well as top-down. Local communities and oppressed groups who bear the brunt of IS’s savagery must mobilize politically and be empowered institutionally in tandem with rather than in contradiction to the efforts from above by states. For example, the U.S.-backed Sunni tribal revolt that defeated IS’s first incarnation in 2007 was not followed by the integration of these forces into Iraq’s state apparatus, rendering the gains made against IS temporary. Similarly, when Syrian rebels — including Islamists — went to war with IS in January 2014, when the president of the exiled opposition coalition Ahmed Jarba proposed a joint U.S.-rebel military campaign against IS June of 2014, and when the Sheitat tribe rose up against IS in August 2014, the U.S. declined to support each and every one of these grassroots initiatives. Thousands of Syrians and Iraqis were slaughtered by IS during its mid-to-late 2014 expansion as a result.

If there is any force fighting IS that adheres to the strategic principles of uniting those who can be united, of waging an international and internationalist struggle, of organizing bottom-up initiatives in tandem with top-down efforts, it is the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) in Syria. Starting in 2012, PYD shrewdly took advantage of the war between the Assad regime and anti-Assad rebels to develop institutions and practices of self-governance in Syria’s Kurdish cantons, Afrin, Kobane, and Jazeera (collectively, Rojava). To gain mass support for, acceptance of, and participation in these institutions and practices from the neighborhood level on up, PYD launched a political coalition, Movement for a Democratic Society (Tev-Dem), and created the YPG (and its all-female counterpart, YPJ) to defend this new system by force of arms. Thanks to years of thoroughgoing bottom-up political work, the PYD-dominated YPG was well placed to become a viable partner with the U.S.-led anti-IS coalition. Relentless YPG-directed U.S. air strikes from above combined with YPG’s heroism from below saved Kobane from IS aggression in fall of 2014. Rojava’s struggle against fascism with jihadist characteristics has inspired a generation of internationalists to join their fight much as the Popular Front’s struggle against Franco inspired the International Brigades. And like its Popular Front predecessor, the YPG has welcomed these internationalists with open arms.

If the fight to save Rojava from the clutches of IS evokes memories of the Spanish civil war, the broader war on IS is reminiscent of World War Two (WW2). Then, leftist forces — the Soviet Union and communist-led underground/partisan movements in fascist-occupied Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy, France, China, and Viet-Nam — worked hand-in-glove with democratic governments and even rightist guerillas in an incredibly complex struggle to defeat Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, and imperial Japan. To defeat IS, the U.S. is working extremely closely with the leftist YPG as well as the partisan-style New Syrian Army, a rebel group whose sleeper cells waged successful assassination campaigns behind enemy lines on the Syria-Iraq border as the White Shroud before becoming U.S.-backed guerillas. Similar assassination campaigns by underground Sunni groups in Mosul show that there are bottom-up initiatives in Iraq that merit similar top-down support.

Just as the closing stages of WW2 saw the Soviets and the Americans race to Berlin, so too will there be a race to seize IS’s capital Raqqa by the rival U.S.- and Russian-led coalitions. Unlike WW2, the war on IS will not end when the enemy’s capital is taken but the struggle will change form. Deprived of state power, IS will lose its fascist characteristics and revert back to what it was before Obama’s foolhardy withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq in 2011 — a military conspiracy plotting mass-casualty attacks financed by an extortion network. Without a territory in which to forcibly impose their barbaric sharia, few foreigners will be inspired to travel to join IS’s jihad, the quantity and quality of IS online propaganda will decline as lavish funding dries up, and the vicious cycle of foreign fighters traveling to IS territory, gaining combat experience, and returning home to launch attacks will eventually grind to a halt. Until then, Western law enforcement agencies simply do not have the manpower to properly monitor every suspected jihadist and successfully thwart every single terrorist plot.

The fight against IS at home begins abroad. The more territory IS loses, the more terrorist attacks it will launch elsewhere and so overthrowing IS rule in Iraq and Syria is an urgent priority for the domestic security of Western countries. However, unless IS’s military defeat and destruction is followed by a durable, comprehensive political settlement in Syria and reconciliation in Iraq, the group will find a way to stage a second comeback.

Reblogged this on YALLA SOURIYA.

LikeLike